Aug 16, 2011

New Releases: 'Beats Rhymes & Life: The Travels of A Tribe Called Quest'

The most shocking moment of Beats Rhymes & Life, Michael Rapaport's look at the rise and fall of one of hip-hop's most influential and eclectic groups, occurs late in the movie. Maseo, a member of De La Soul, performing with A Tribe Called Quest at 2008's Rock the Bells tour (where estranged members Q-Tip and Phife Dawg reunited for what were allegedly their last live performances), is asked if he thinks Tribe will ever play in front of an audience again. “I hope not,” is his immediate, unexpected answer—and this coming from one of the group's most devout, respectful admirers.

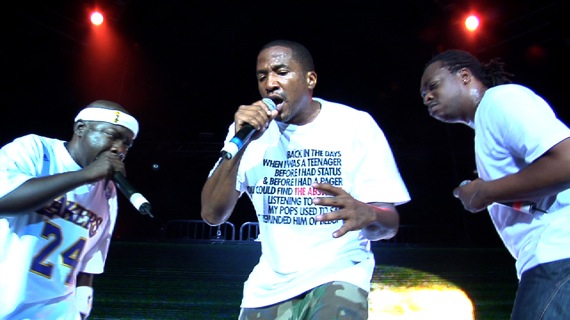

By this point, antagonism between Q-Tip—acting as unofficial frontman, confident, charismatic, perfectionist—and Phife Dawg—ingratiating and often quiet, suffering from diabetes but addicted to sugar—had festered to its breaking point. Surprisingly candid behind-the-scenes footage at the 2008 Rock the Bells tour shows the duo (the two MCs behind some of the most memorable rap songs of all time) physically confront each other immediately before they're supposed to perform. In this light, Maseo's confession that he'd rather not see the two perform together again makes disheartening sense: their rivalry can only cast a suffocating shadow over what had been, years earlier, one of the most fertile partnerships in hip-hop.

How had things gotten to this point? Eighteen years earlier, A Tribe Called Quest released their first full-length album, People's Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm, and almost instantaneously changed what rap could sound like. The album provided two singles that would become unforgettable landmarks in the history of rap—“Bonita Applebum” and “I Left My Wallet in El Segundo” (the title of which, Q-Tip confesses, came from a recurring joke on the show Sanford & Son)—but the songs “Luck of Lucien” and “Can I Kick It?” arguably provide the album's highlights. (“Can I Kick It?” in particular provides a seemingly incontrovertible case for the art of sampling: the Lou Reed snippet that provides the song's hook is completely transformed by Tribe's lush production.) The ensuing years would see the release of two subsequent masterpieces, 1991's The Low End Theory and 1993's Midnight Marauders, which would cement Tribe's place in the annals of rap history. The beats on all three of these albums were jazzy, obscure, complex, and perfectly complementary to the group's smooth style; as one interviewee notes, their productions heavily sampled the unheard-of jazz LPs hidden away in their parents' record collections, which few other producers had sought out before. (This eclectic sound is one way, among many, that Tribe's influence may be detected in the later productions of Kanye West, Madlib, DJ Premier and Pete Rock, among many others.) The rhymes, meanwhile, were equally obscure, bizarre abstractions and non-sequiturs, smoothly delivered, without pretense, seemingly transplanted from some parallel alternate dimension. While many other groups were leaning towards violent manifestations of a life of crime or impassioned commentaries about the life of black people in the United States (Public Enemy, Gang Starr, NWA, or even Wu-Tang Clan, whose debut Enter the 36 Chambers was released the same day as Midnight Marauders), A Tribe Called Quest remained tantalizingly playful, even otherworldly.

Their music is so good one almost wishes Beats Rhymes & Life would concentrate on it more. While the process of making these three landmark albums is briefly outlined (including an excellent scene in which Q-Tip explains how he retrieved the drumline for “Can I Kick It?” from an old Lonnie Smith record), and a lineup of modern-day rap figures respectfully details the group's lasting influence, these formative early years are skimmed over in order to get to the bitter dramatic conflicts that defined the group's later years. But this is a gripe coming from a hardcore fan of the group who, confessedly, heard a few strains of “Excursions” in the documentary and mostly just wanted to listen to The Low End Theory from beginning to end. There's a lot packed into this 97-minute film; in fact, Rapaport finds an excellent balance between adulation and brutal honesty for both neophytes and faithful Tribe fans. (It helps that Rapaport is obviously an enthusiastic fan himself, especially judging from the attention he gives to Phife Dawg's outstanding verse on “Buggin' Out.”)

Tempers rose following the release of Midnight Marauders. Phife Dawg moved to Atlanta (partially due to his ailing health, as he struggled to overcome his addiction to sugar) while Q-Tip and beatmaker/DJ Ali Shaheed Muhammad remained behind in their native Queens. (Jarobi, who is sometimes considered an unofficial member of the group, had already bowed out beforehand.) It's difficult to describe exactly what led to the falling-out between Q-Tip and Phife; even the two musicians seem to have trouble doing so throughout Beats Rhymes & Life. But the answer may be found in their respective personalities: throughout the documentary, Q-Tip is emphatic, charismatic, controlling, boastful, while Phife Dawg is quiet, modest, sensitive, and ailing. Increasingly resentful of Q-Tip's self-appointed rise to leader of the group, Phife nonetheless contributed verses to their ensuing albums and performed live with Q-Tip and Muhammad, but became angry with Q-Tip's rigorous perfectionism. Accusations were flung in the press, particularly by Q-Tip, though he continues to insist that his words were taken out of context. It all culminated in 2008's Rock the Bells tour, during which Q-Tip seems to call out a sickly Phife Dawg's lackluster performance onstage, leading to a near-physical altercation backstage.

Like 2004's Metallica: Some Kind of Monster, Beats Rhymes & Life vividly portrays the inflated egos and impassioned altercations that rage in the background of the creative process. To my admitted surprise, I liked the Metallica documentary—I've never considered myself even remotely enthusiastic about their music. I've been a fan of A Tribe Called Quest, on the other hand, basically since I started listening to hip-hop in high school, and Beats Rhymes & Life functions reasonably well as a commemoration of the group, and extraordinarily well as an exposé of their unfortunate fallout. The personalities of all four members of the group come across vividly, giving further vibrancy to the music they created (which in any case remains among the most creative and exciting ever made in the rap world).

The documentary form should conceivably excel at characterization, offering real-life figures the chance to shape their own narratives onscreen; more realistically, though, documentary filmmakers shape these narratives form them, and sometimes end up neglecting the personalities of their subjects with a dreary obedience to traditional narrative form and an overly literal pursuit of objectivity (provided, mundanely, by an assortment of talking heads or an over-reliance on archival footage). Beats Rhymes & Life avoids the pitfall that many documentaries succumb to, especially music documentaries—it does not always strive for an objective portrayal of the facts, instead relying upon its own electrifying cast of characters for a certain account of the facts. It's a human drama, and it never tries to pretend otherwise.

This becomes especially clear in the case of Ali Shaheed Muhammad, the group's DJ, who remains a cypher throughout the film. This could have been a drawback if it had been a deliberate attempt on Rapaport's part to foreground the two larger-than-life MCs. But Muhammad is given numerous chances to speak for himself and, instead of giving in to the vicious rivalry erupting between Q-Tip and Phife Dawg, remains neutral, peaceful, respectful and admiring of them both. He is, as Phife's wife notes at one point, a friend unfortunately caught in the middle; when Mary J. Blige showers praise upon Muhammad and A Tribe Called Quest at one point (he's helping to produce one of her albums), he simply smiles, somewhat sadly, aware that they've made incredible music and have degenerated into a squabbling family. The most powerful moment in the movie may be a candid shouting match between De La Soul's Posdnuos and Q-Tip in a backstage room at the Rock the Bells tour; while the two musicians lament what A Tribe Called Quest has come to, the camera happens to pan across Muhammad's face—then stays there. The two outspoken men remain off-camera as Muhammad stares at the ceiling, obviously frustrated but saying nothing. He appears oblivious to the fact that the camera is recording him, which, maybe, is why he offers such a humane and subtle expression of annoyance and sadness. Like Q-Tip and Phife Dawg, Muhammad exhibits a lived-in, vivid personality that remains unknowable, and it's a testament to the movie that it respects his privacy, never trying to pry from him a testimony he wouldn't otherwise give.

After all of this candor, this unflinching study of a group in dissolution (and from a diehard fan, no less), the ending of Beats Rhymes & Life seems to stumble a bit. The movie does not conclude with the disheartening Rock the Bells tour in 2008—an epilogue actually picks back up in 2010, when a seriously ailing Phife discovers that his wife happens to be a perfect match for the kidney transplant he needs to survive. An excellent (and surprisingly powerful) scene in the hospital shortly before Phife's operation reveals to us that Q-Tip sent a brief text message to Phife (which remains unseen to us)—nothing elaborate, just an amicable reaching-out, wishing him luck with the transplant. I wish the movie had ended here: on a note of optimism, with Phife realizing how blessed he is with a loving family and recovering health (and hinting towards the reconciliation that Phife and Q-Tip may still work at).

Instead, the documentary follows A Tribe Called Quest as they reconvene for one last tour (this time in Japan). As the group plays to sold-out stadiums and (somewhat absurdly) practices their choreography at rehearsals, Rapaport seems to suggest that the magic has been recaptured, that A Tribe Called Quest may be in the middle of their comeback. (An onscreen title even informs us hopefully that Tribe still has one record remaining on their original contract with Jive Records.) I understand (and sympathize with) Rapaport's desire to celebrate the group's reunion, but a lot of onscreen evidence in this last sequence simply doesn't support it. When Phife and Q-Tip initially meet again, for example, they nod tersely and embrace briefly; then Tip simply walks away to shake hands with Muhammad. Some canny editing tries to convince us that the group's Japanese tour is as electrifying as their original shows in the early 90s, but we're not fooled: the group obviously (and inevitably) just doesn't have the spark they once did.

But even if the end of the movie's rose-colored optimism is unconvincing (and too self-conscious), we are still reminded of the heights that hip-hop can rise to at its best, and we (arguably) also realize that no rap group since Tribe has come close to matching their playfulness, their eccentricity. Indeed, by trying to make Beats Rhymes & Life appeal to everyone imaginable, Rapaport may have made a documentary that's almost too streamlined for this one-of-a-kind group. (Imagine, for example, a film that would have played on the level of “Check the Rhime” for 100 minutes.) But, as mentioned before, Beats Rhymes & Life is trying to tell a larger-than-life human drama, not blow your mind with some Sun Ra-ish fantasia, so I suppose it doesn't make sense to criticize it for being overly conventional. Earlier masterpieces like Scratch and Style Wars—the two best movies about hip-hop ever made—strike an extraordinary balance between mass appeal and one-of-a-kind, mind-bending styles; Beats Rhymes & Life manages a feat that's nearly as impressive—fleshing out the human drama behind one of the most legendary groups in the history of rap.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)