This post is the first in a new series I'm starting: viewings and responses to films released as close to thirty years ago as possible. The first entry is Sidney Lumet's Prince of the City, originally released by Orion Pictures and Warner Bros. on August 21, 1981. (Yeah, I'm a little late on this one—I have a busy work week to blame.) I hope these posts will offer a snapshot of the cinematic and social climate in 1981, and will be an interesting way to chart developments and/or innovations in film since then.

Why 1981, one might ask? Two reasons, both of them mostly arbitrary. The first is that I have often neglected films of the 1980s and early 1990s much more than any other historical era—while I've enthusiastically explored silent film, classics of the early sound era to the mid-twentieth century, and developing New Waves and changes in international cinema in the 1960s and 1970s, I for some reason have been mostly uninterested in films of the 80s and 90s, until now. Secondly, I was born in 1984 and did not really start paying attention to movies as a social art form until the late 1990s, so I feel like it will be interesting to further explore and chart the changing cultural climate of the era into which I was born.

Prince of the City 167m., R, USA

Release Date August 21, 1981

Distributors Orion Pictures & Warner Bros. Pictures

Director Sidney Lumet

Writers Jay Presson Allen and Sidney Lumet, based on the book by Robert Daley

Producers Jay Presson Allen and Burtt Harris

Music Paul Chihara

Cinematography Andrzej Bartkowiak

Editor John J. Fitzstephens

Production Design Tony Walton

Cast Treat Williams, Jerry Orbach, Richard Foronjy, Don Billett, Kenny Marino, Carmine Caridi, Tony Page, Norman Parker, Paul Roebling, Bob Balaban, James Tolkan, Steve Inwood, Lindsay Crouse, Matthew Laurance, Tony Turco, Ron Maccone, Ron Karabatsos, Tony DiBenedetto, Tony Munafo, Robert Christian, Lee Richardson, Lane Smith, Cosmo Allegretti, Bobby Alto, Michael Beckett, Burton Collins

Commercially unsuccessful and middlingly reviewed upon its release (it was deemed inferior to Lumet's 1973 crime drama Serpico), Prince of the City is now generally seen as one of Lumet's strongest hours (or, to be more precise, nearly-three-hours). And that it is, though I don't consider myself one of the director's fans: too often, he oversells visual metaphors with a deadening obviousness, and he sometimes allows his actors to overplay or to encapsulate their characters in broad, simple character traits. While his background in directing TV series and made-for-television movies in the 1950s and '60s can lend his films a swift, tough conciseness, it can also make them overly schematic in their narrative arcs—as though he were still working under the rigorous scheduling and episodic demands of working for a television studio. (This blueprint-following brand of filmmaking especially hampers his 2007 film Before the Devil Knows You're Dead.)

But it's easy to dismiss such quibbles in the context of Lumet's long career, which undeniably expressed the cohesive style and thematic concerns of an unassuming auteur. The director (who passed away less than five months ago, on April 9th) offered us at least two great films, 12 Angry Men (1957) and Dog Day Afternoon (1975), and several almost-great ones (Network [1976], The Verdict [1982]). He has been deemed one of the quintessential "New York directors"—not unlike Martin Scorsese or Woody Allen, the director's adopted hometown is a driving character in many of his films. Some of his works would be inconceivable set in another city. He also returned consistently to the theme (which always fascinates me) of how large-scale institutions (television networks, police forces, urban governments, the court system, hospitals and health care) influence the lives of individuals embroiled within that system—and, correspondingly, how individuals may actively resist or refashion those systems.

Prince of the City is one of the finest examples in Lumet's filmography of both of these tendencies. His status as a New York filmmaker has never been more impressively displayed than in this film: the city is an indelible backdrop here, a writhing, squalid creature that instills moral crises in more than a few characters. The aspect of Prince of the City I'll likely remember more vividly than any other is its encapsulation of a pre-Giuliani New York, a snapshot of a city that could not be more foreign to us than the New York we now know. Like the city as seen in Taxi Driver (1976), Chantal Akerman's News from Home (1977), or Bette Gordon's Variety (1983), New York here is a grittily evocative contradiction: glittering and disgusting, monumental and festering, impressive and disheartening. Prince of the City is absolutely a product of its time and place, which here should be taken as a thunderstruck compliment rather than a disparagement—it is the most immersive portrayal of New York in its Ed Koch days that I've ever seen.

The film is also a complex, sprawling document of the ways that numerous forces of law and order interacted (and, to an extent, still interact) in the city. The story concerns an esteemed narcotics agent, Danny Ciello (Treat Williams), who undergoes a crisis of conscience (and self-identity) and decides to work with the FBI's Chase Commission in exposing corrupt agents on the New York police force. Like any other undercover narcotics agent at the time, Ciello relies upon addicts and junkies for information, often being forced to supply them with hard drugs in order to get them to cooperate (and, more distressingly, simply to survive). One of the film's strongest scenes is his excursion to the underbelly of Manhattan at three in the morning to console an informant suffering from withdrawal; rescuing the shivering, desperate man from a grimy alleyway during a rainstorm, Ciello drives him from one supplier to another, looking for anything that will placate him (heroin, coke) and keep him in Ciello's good graces. Eventually, Ciello winds up chasing down another junkie named Jose, beating him mercilessly in order to score two bags of coke for his informant. Shortly thereafter, Ciello, in the midst of self-loathing, drives Jose to a decrepit rattrap of an apartment covered with graffiti—then simply watches in helpless horror as Jose beats his girlfriend for getting high off of his stash. Swiftly and unforgettably, Prince of the City evokes a cesspool of a world in which the close relationship between narcs and junkies makes it easy, as Ciello later confesses, to mistake heroes for villains, right for wrong—to commit unspeakable acts and defend them, sometimes self-righteously, as ultimately moral behavior.

It is this blurring of previously absolute moral codes that leads Ciello to provide testimony to federal agents investigating corruption. Initially, he is told that their targets will be the true overlords of the urban drug trade: wealthy suppliers, lawyers, judges, mayors, city officials that are bought off in order to look the other way, or even to facilitate the profitable narcotics industry. Ciello is immediately (and, as it turns out, rightly) distrustful of the agents who approach him, including Rick Cappalino (Norman Parker), a kind, mild-mannered young agent who genuinely respects and empathizes with Ciello but has no way to defend him from the manipulations of the system in which they find themselves. (Parker gives what may be the most sensitive performance in the whole movie, which seems amazing to me—I had never heard of him before, and besides this film he appeared mostly in television series.) Ciello vociferously tells the FBI he will never betray the trust and camaraderie of his partners in narcotics, he will never rat on them, and at first he is told he will never have to. But of course, as powerful corporate and business agents are targeted by the FBI and exposed by Ciello, accusations against him and his squad force him to expose their past indiscretions—confessions which ultimately have deadly, soul-shattering consequences.

The brotherhood between Ciello and his partners—and the antagonism between Ciello and the federal agents who work for the Chase Commission (and, especially, between Ciello and the prosecutors who consider him a corrupt rat but still hypocritically rely on his testimonies)—is powerfully established by a huge and mostly impressive ensemble cast. Countless crime dramas and police stories have been about the unbreakable bond between the partners who work together, but rarely has that bond been as believable as in Prince of the City. Even when Ciello is initially pressured to deliver information about fellow cops, he tells his partners (drunkenly, despondently), and they respond to him with understanding, sensitivity. (An abrupt cut to a low-angle close-up of Ciello on the brink of madness and self-disgust in this scene is devastating.) They still don't believe he could or would ever betray them. The fact that he inevitably does is an indictment not against Ciello but against the system: the faceless, interconnected network of corporate, government, judicial, and police institutions that conspire to exploit one man in order to obtain a conviction, to offer their functionaries promotions, or to protect or dismantle a lucrative criminal enterprise.

Prince of the City is the most thematically complex of Lumet's movies I've seen—there's actually much more to be said about the film's employment of characters emblematic of different social forces and how they respond to and coerce Ciello's behavior. (He's a man who mistakenly believes he's in control of his own fate, his own morality—the movie is tragic partially because he eventually realizes how untrue this is.) It's tempting to claim that a movie like this—so long, so complex, so dark in tone and subject matter, so attuned to character and to societal forces—could no longer be bankrolled by a major studio, but this isn't exactly true: recent epic crime dramas like Zodiac (2007) and The Dark Knight (2008—more allegorical but almost as insightful) remind us that signs of creativity, intelligence, and power can still be found in Hollywood action movies.

What may be peculiarly early-80s about Prince of the City, though (aside from its garish costuming—itself a time-capsule wonder to behold, or bemoan), is its stylistic simplicity, its un-flashiness. Again, this may be largely the result of Lumet's origins in television, which serve the atmosphere and elaborate themes of Prince of the City extremely well. It seems like most crime dramas made today would be distinguished by a certain aesthetic panache: to return to the two examples above, Zodiac abounds in David Fincher's elaborate, sleek, razor-sharp form (though at least there it serves a purpose), and The Dark Knight delivers its themes through operatic superhero machinations. Or we may think of Michael Mann's so-beautiful-they're-hollow digital compositions (in his movies, the overabundance of style is itself a form of substance), or the self-conscious grittiness of movies like Narc (2002) or We Own the Night (2007), with their grainy handheld cinematography.

While Lumet does include a few stylistic flourishes—like cuts to the identification cards of policemen or federal agents accompanied by throbbing electronic music, or quotes from Robert Leuci, the narcotics officer who was the real-life inspiration for Ciello, splayed at the bottom of the screen in bold newspaper-esque lettering—for the most part his aesthetic choices are subtle, careful, well-thought-out. He gives the impression of a documentary-like remove from the material, but his cutting between expanded extreme long shots in wide angle (which make the characters near-microscopic), solid, static medium shots that simply observe groups in conversation, and emphatic close-ups of characters at the height of self-loathing or desperation reveal a sensitive knowledge of the material's emotional and psychological undercurrents. It doesn't seem overblown to claim that Lumet's style here is reminiscent of the precise yet "invisible" style practiced by classical Hollywood masters like William Wyler or Anthony Mann, though the subject matter is considerably (and justifiably) darkened and deepened for its early-1980s setting.

The weakest aspect of the movie, as I see it, is Treat Williams's performance in the lead, though this is something I'm still debating: his performance is either completely original or drastically off-base in its interpretation of Ciello's early moral crisis. There's a manic energy to it that seems miscalculated early on, though this desperation makes more sense as the movie progresses and Ciello becomes increasingly distraught by guilt, moral confusion, and self-disgust. An early scene has Williams shouting to the proverbial rafters, rabidly defending his impending actions to two federal agents, in a long and frankly irritating scene; the point, it seems, is to recognize Ciello's fraught attempts to rationalize his inner conflicts, his bipolar attitude towards the ethical leap and calamitous risk he's about to take, but this could be conveyed in a manner more subtle, more believable, and more in tune with how the character behaves at this early point in the film. I wonder if this style of overacting, of absolute self-abandonment and immersion, is something more common in movies of the late 1970s and 80s—a time, perhaps, when previous theories of Method acting coalesced with the expressive aesthetic techniques of American New Wave directors like Scorsese, Brian De Palma, and Francis Ford Coppola. After all, this bombastic acting style also irrevocably harmed Lumet's Serpico—a film that features such an overblown Pacino performance it's impossible to believe in the main character as a real human being (obviously, a quality that does not work well in a character study). In any case, my ambivalence towards Williams's performance corresponds strangely well to the movie's own ambivalence towards the character of Ciello—to the film's credit, it never decides absolutely whether its protagonist is a selfless moral crusader or a self-righteous hypocrite, a moral complexity that is unforgettably envisioned by the final freeze frame.

Sep 2, 2011

Aug 27, 2011

Classics: 'La Ronde' (1950) and 'The Earrings of Madame de...' (1953)

|

| Max Ophuls |

The pertinent question, maybe, is whether or not Ophüls' characters, ideas, and emotions are as beautiful as his camera movements—or, really, whether they're more than just beautiful, whether there's some tumult, some crisis, that affects us as powerfully as the aesthetic does. After all, Ophüls' films typically concern absurdly elegant aristocrats existing in a historical period (in La Ronde and The Earrings of Madame de..., late-19th and early-20th century Europe), struggling to cope with calamitous affairs of the heart, suffering from love and lust and heartache but ever maintaining a veneer of beauty and untouchability in the process. For Ophüls' detractors, these movies are about dilettantes who modern (especially middle- or lower-class) audiences couldn't care less about—characters defined more by their prettiness than by their emotions. For his legion of avid admirers, though—which included, famously, Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris (this may have been the one subject both of them agreed upon)—Ophüls broke through the brittle shell of aristocratic respectability to show the pain and maddening desire that lingered underneath. His always-roaming camera, they argued, patiently observed the possessions and elegant environs of wealthy characters to emphasize the significance of small tokens, tangible things, as they fit into turbulent lives. They were accoutrements for people, but also embellishments for a sort of cosmic cycle of desire, love, and loss—props in a vast and tragic comedy seemingly staged for God's own amusement. The predominance of things and decorations in Ophüls' films also act as juxtapositional foreshadowing: their houses and their belongings may be in order, but everything else (everything inside) is in disarray.

It seems fans of Ophüls are rarely timid in their enthusiasm: many celebrations of the director proclaim him the most beautiful, the most humane, the most sensitive and underappreciated visionary in the history of movies. (Molly Haskell, in this excellent essay, lauds Ophüls as a defender of unassuming heroes and heroines, Stendhalian characters whose freedom and wealth are tenuous and unstable—values that could be forsaken in an instant for love and passion.) I may not go quite so far in my praise for the director, but I am (after seeing these two films, and with fond memories of his 1948 American movie Letter from an Unknown Woman still popping up constantly) unequivocally a fan. His camera movements and his characters may be pretty, but both the style and the characters are hiding something considerably painful underneath.

|

| La Ronde |

Admittedly, this may be harder to detect in La Ronde than in either Letter from an Unknown Woman or The Earrings of Madame de.... Ophüls' 1950 film was the first he made back in France after his brief tenure in Hollywood (which wielded a small number of too-little-known gems), and, as Terrence Raferty points out, La Ronde exhibits Ophüls in a playful, unabashedly wry manner that epitomizes his “European” sensibilities. (Usually, that descriptor means nothing and reeks of ethnocentrism, but with Ophüls it actually makes sense: a born German who worked in his home country, France, Austria, Italy, and the Netherlands as well as the U.S., he shared a cosmopolitan world-weariness, the bittersweet displacement of a refugee from his own land, and a sympathetic romantic fatalism with his European countrymen—although the winking self-consciousness displayed in La Ronde is a little closer to American comedies of the time.)

La Ronde is adapted from a notorious Arthur Schnitzler play that was written in 1897, finally performed in Budapest in 1912, and eventually staged in Schnitzler's hometown of Vienna in 1921. The play concerns a sexual merry-go-round, traversed over ten scenes, ingeniously plotted: in the first, a prostitute makes love to a soldier; in the next, the soldier seduces a seemingly naïve young chambermaid (who reveals herself to be more headstrong than we may have assumed); in the next, the chambermaid is taken by her fumbling employer; and so on, until the licentious cycle (“the ring” of the title) completes itself.

Ophüls' film adaptation introduces a new character: an elegantly bemused, disarmingly meta narrator who operates a literal merry-go-round as the sexual cycle rages on around him. In the first scene, this narrator takes us behind the camera, noting the artificiality of the studio set, even pointing out the lighting setups and cameras before the film itself gets underway. Later, Ophüls will cut to this narrator at the exact moment that a young male character (who fancies himself a virile stallion) is unable to perform in bed; after tinkering with the mechanics of the carousel for a minute, however, the narrator is able to kickstart the young man's libido and thrust the carousel back into motion. There's even another scene in which the narrator can be seen cutting an explicit sequence from a strip of celluloid with a pair of scissors—Ophüls finds numerous ways to dance around onscreen sex in this film, with characteristic flair and cleverness.

Although there are melancholy sequences (the best scene in the film is an uneasy dialogue between an aged, wealthy aristocrat and his young, beautiful wife, who realize, through evasive and somewhat defensive testimonies, that they still care for each other after years of sexless marriage), the overall tone of La Ronde is spry and relatively carefree. The film is, of course, about rampant infidelity and unimpeded lust, but the audience never sees any tearful fallouts between lovers because of this disloyalty. We witness instead, as the narrator points out, the familiar machinations of the game of sex: amorous men and women playing off of each other, embodying all manner of lust and flirtation and desire. The central metaphor is, of course, that carousel, but we may also think of a chessboard: one of the movie's prime delights is that we can chart the characters' strategic come-ons and invitations, reveling in the excitement of sex as a game to be played.

This may all sound very icy and hollowly clever, but for all of its lasciviousness, La Ronde is surprisingly sweet. The most charming sequence in the film may also be the most aesthetically impressive: a prolonged flirtation between an awkward young man-of-the-house and his beautiful chambermaid, who bat double entendres back and forth as they circle around each other in a vast drawing room. When their mutual attraction makes itself clear, the camera dazzlingly follows the young man as he half-runs to all of the windows in the room, drawing the shutters closed. (This scene is also incredibly sexy, thanks mostly to Simone Simon as the chambermaid, Marie.) There may not be much to La Ronde besides its effortlessly elegant sense of humor, its dazzling camerawork, and engaging performances by a huge international cast. In other words, it's light as air, but that happens to be enough: Ophüls' enthusiasm for the art of moviemaking as well as for the romantic games people play becomes contagious almost immediately.

|

| The Earrings of Madame de... |

If La Ronde is a somewhat lightweight offering from an undeniable master craftsman, then The Earrings of Madame de..., made three years later, is a tremendously powerful film that expands and deepens its creator's sensibility. I may still prefer Letter from an Unknown Woman, which burns with unattainable desire and the passion of mad love, but I have to admit that Madame de... may be the more sensitive film: all three of its main characters are the Stendhalian protagonists that Haskell cited—unheroic people who think they are free and happy, only to realize how trapped and unfulfilled they really are, forsaking everything for a taste of true love and passion.

“There is no happiness in joy,” says a character in another Ophüls film, Le Plaisir—a sentiment that helps to explain the melancholy power of Madame de.... The titular Countess (who remains unnamed throughout the movie—her plight is universal, not confined to the wealthy) sells the earrings that were given to her by her husband on their wedding night. At the beginning of the film, they obviously mean little to her; yet, as the film progresses, they take on greater emotional significance (both for her and for the audience), especially when they are re-gifted to her, through a taunting twist of fate, by a dashing Italian Baron with whom she is helplessly in love. The sequence in which the Countess and the Baron Fabrizio Donati waltz, night after night, falling deeper into the throes of love and passion, is rightfully celebrated as one of the most sublime in the history of movies: a series of dissolves orchestrates the temporal movement of the editing with the spatial movement of the gracefully-waltzing camera, as weeks are compressed into minutes and helpless passion is somehow, miraculously, visualized. The sequence seems effortless, light as air, but was clearly very meticulously planned out. Like the dance numbers in Swing Time or Top Hat—which seem similarly effortless but took months of preparation for Astaire and Rogers to perfect—the ballroom scene in The Earrings of Madame de... makes us believe that it's possible to convey the deepest love onscreen. (Maybe the most gifted composer can suggest passion sonically, and maybe the most brilliant writer can suggest its unequaled beauty, but don't movies seem especially suited to conveying such an inexpressible emotion?)

Lest we assume The Earrings of Madame de... is just a beautiful movie about beautiful people falling in love, it's actually about how impenetrable these characters assume themselves to be, and how perfect they consider their lives to be. At first, admittedly, we may be put off by these characters. The Countess is selfish and manipulative; she knows how to play off of the men around her (including, and especially, her husband), staging fainting fits and flirting publicly with aristocrats, confidently aware of her standing in the Parisian upper class. She's not really vilified—she's simply abiding by the expectations and opportunities afforded to her in 1900 Paris. We sympathize with her inflexible social position and the behavior expected of her, but we also are dismayed by the value she places in material objects (and, maybe, the extent to which she sees other people as material objects). Her husband, an esteemed General, is hardly more likeable: a tyrant who is aware that his wife no longer loves him, the General simply accepts this as a consequence of aristocratic marriage in his society, finding social standing more valuable than intimacy between a husband and wife. All of this changes when the Baron enters the scene, however. Lives of shallow materialism and invincible pride are suddenly revealed to be empty; people and possessions are discovered to have real value. Those telling earrings reveal to the Countess how shallow her life had been; they reveal to the General how powerless he was over his wife, precisely because there was no love between them; and they reveal to the Baron how willing he is to sacrifice everything for a love he knows can never be recognized by society. If Ophüls' films can be accused of a sort of aristocratic aestheticism, The Earrings of Madame de... would seem to absolutely deflate that criticism: all of the beauty and wealth of their lives revealed to be totally meaningless.

Here, the agile camera movements are in the service of the actors, the characters: no stylistic flourish exists for its own sake. The glacially-paced tracking shot that opens the movie, which scans the Countess's jewelry and clothes like an auctioneer appraising goods, reveals how little these possessions mean to her; a remarkably swift camera during the scene in which the Countess and the Baron first meet (at a Parisian customs office) conveys the excitement, the giddiness, that the Baron feels upon first seeing her.

As sensitive as Ophüls is—and as finely tuned as Christian Macras's cinematography is to the movements and sentiments of the characters—the film may ultimately excel because of its cast. Is Danielle Darrieux's Madame de... one of the most romantic, tragic, unexpectedly powerful characters in the history of movies? The smoothness of her features, the deepness of her eyes, define elegance, yet she flawlessly allows traces of her sadness, her despair, her restrained passion, to suggest themselves. I was unsure of how much the movie would affect me emotionally until relatively late in the film, when, at a ball, the Countess is simultaneously spurned by the Baron (who finally discovers the real origins of the earrings he gave her as a gift) and forbidden to wear those earrings by her jilted husband. Darrieux's absolutely deflated performance in this scene is heartbreaking, especially because she so desperately struggles to maintain a semblance of elegance and cool resolve. Charles Boyer, meanwhile, as her husband—the cold, confident, yet not unfeeling General—uses his untroubled demeanor to present a man totally unwilling to believe there are cracks in his hypothetically perfect life. Boyer is no less excellent at allowing fractions of pain and jealousy to sneak into his cool stoicism. (Boyer and Darrieux had played lovers in the 1936 film Mayerling, by Anatole Litvak. It was a huge success, and almost twenty years later, the memory of their onscreen chemistry must surely have affected audiences seeing The Earrings of Madame de...—as though the couple who fell in love in Mayerling would eventually become the distant husband and wife seen in Ophüls' film.) And finally, the great director Vittorio De Sica, incomparably dashing and hopelessly romantic as the Baron, epitomizes one of those aforementioned “small heroes”—a man who has the bravery to simply obey passion, give in to love, though he knows without a doubt that it will destroy him.

The immediate pleasures of Ophüls's filmmaking—the silky, acrobatic black-and-white cinematography, the lush costumes, beautiful actors, opulent set design, meticulous plotting—may bring some viewers to the assumption that its style is more than its substance, that the director's humanity, his characterizations, couldn't possibly compare to his virtuoso aesthetic. Maybe not—but in Letter from an Unknown Woman and The Earrings of Madame de..., they come close. There is no joy in happiness; beauty has never been so sad.

Aug 16, 2011

New Releases: 'Beats Rhymes & Life: The Travels of A Tribe Called Quest'

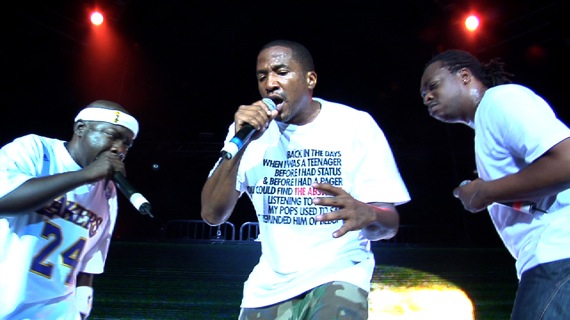

The most shocking moment of Beats Rhymes & Life, Michael Rapaport's look at the rise and fall of one of hip-hop's most influential and eclectic groups, occurs late in the movie. Maseo, a member of De La Soul, performing with A Tribe Called Quest at 2008's Rock the Bells tour (where estranged members Q-Tip and Phife Dawg reunited for what were allegedly their last live performances), is asked if he thinks Tribe will ever play in front of an audience again. “I hope not,” is his immediate, unexpected answer—and this coming from one of the group's most devout, respectful admirers.

By this point, antagonism between Q-Tip—acting as unofficial frontman, confident, charismatic, perfectionist—and Phife Dawg—ingratiating and often quiet, suffering from diabetes but addicted to sugar—had festered to its breaking point. Surprisingly candid behind-the-scenes footage at the 2008 Rock the Bells tour shows the duo (the two MCs behind some of the most memorable rap songs of all time) physically confront each other immediately before they're supposed to perform. In this light, Maseo's confession that he'd rather not see the two perform together again makes disheartening sense: their rivalry can only cast a suffocating shadow over what had been, years earlier, one of the most fertile partnerships in hip-hop.

How had things gotten to this point? Eighteen years earlier, A Tribe Called Quest released their first full-length album, People's Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm, and almost instantaneously changed what rap could sound like. The album provided two singles that would become unforgettable landmarks in the history of rap—“Bonita Applebum” and “I Left My Wallet in El Segundo” (the title of which, Q-Tip confesses, came from a recurring joke on the show Sanford & Son)—but the songs “Luck of Lucien” and “Can I Kick It?” arguably provide the album's highlights. (“Can I Kick It?” in particular provides a seemingly incontrovertible case for the art of sampling: the Lou Reed snippet that provides the song's hook is completely transformed by Tribe's lush production.) The ensuing years would see the release of two subsequent masterpieces, 1991's The Low End Theory and 1993's Midnight Marauders, which would cement Tribe's place in the annals of rap history. The beats on all three of these albums were jazzy, obscure, complex, and perfectly complementary to the group's smooth style; as one interviewee notes, their productions heavily sampled the unheard-of jazz LPs hidden away in their parents' record collections, which few other producers had sought out before. (This eclectic sound is one way, among many, that Tribe's influence may be detected in the later productions of Kanye West, Madlib, DJ Premier and Pete Rock, among many others.) The rhymes, meanwhile, were equally obscure, bizarre abstractions and non-sequiturs, smoothly delivered, without pretense, seemingly transplanted from some parallel alternate dimension. While many other groups were leaning towards violent manifestations of a life of crime or impassioned commentaries about the life of black people in the United States (Public Enemy, Gang Starr, NWA, or even Wu-Tang Clan, whose debut Enter the 36 Chambers was released the same day as Midnight Marauders), A Tribe Called Quest remained tantalizingly playful, even otherworldly.

Their music is so good one almost wishes Beats Rhymes & Life would concentrate on it more. While the process of making these three landmark albums is briefly outlined (including an excellent scene in which Q-Tip explains how he retrieved the drumline for “Can I Kick It?” from an old Lonnie Smith record), and a lineup of modern-day rap figures respectfully details the group's lasting influence, these formative early years are skimmed over in order to get to the bitter dramatic conflicts that defined the group's later years. But this is a gripe coming from a hardcore fan of the group who, confessedly, heard a few strains of “Excursions” in the documentary and mostly just wanted to listen to The Low End Theory from beginning to end. There's a lot packed into this 97-minute film; in fact, Rapaport finds an excellent balance between adulation and brutal honesty for both neophytes and faithful Tribe fans. (It helps that Rapaport is obviously an enthusiastic fan himself, especially judging from the attention he gives to Phife Dawg's outstanding verse on “Buggin' Out.”)

Tempers rose following the release of Midnight Marauders. Phife Dawg moved to Atlanta (partially due to his ailing health, as he struggled to overcome his addiction to sugar) while Q-Tip and beatmaker/DJ Ali Shaheed Muhammad remained behind in their native Queens. (Jarobi, who is sometimes considered an unofficial member of the group, had already bowed out beforehand.) It's difficult to describe exactly what led to the falling-out between Q-Tip and Phife; even the two musicians seem to have trouble doing so throughout Beats Rhymes & Life. But the answer may be found in their respective personalities: throughout the documentary, Q-Tip is emphatic, charismatic, controlling, boastful, while Phife Dawg is quiet, modest, sensitive, and ailing. Increasingly resentful of Q-Tip's self-appointed rise to leader of the group, Phife nonetheless contributed verses to their ensuing albums and performed live with Q-Tip and Muhammad, but became angry with Q-Tip's rigorous perfectionism. Accusations were flung in the press, particularly by Q-Tip, though he continues to insist that his words were taken out of context. It all culminated in 2008's Rock the Bells tour, during which Q-Tip seems to call out a sickly Phife Dawg's lackluster performance onstage, leading to a near-physical altercation backstage.

Like 2004's Metallica: Some Kind of Monster, Beats Rhymes & Life vividly portrays the inflated egos and impassioned altercations that rage in the background of the creative process. To my admitted surprise, I liked the Metallica documentary—I've never considered myself even remotely enthusiastic about their music. I've been a fan of A Tribe Called Quest, on the other hand, basically since I started listening to hip-hop in high school, and Beats Rhymes & Life functions reasonably well as a commemoration of the group, and extraordinarily well as an exposé of their unfortunate fallout. The personalities of all four members of the group come across vividly, giving further vibrancy to the music they created (which in any case remains among the most creative and exciting ever made in the rap world).

The documentary form should conceivably excel at characterization, offering real-life figures the chance to shape their own narratives onscreen; more realistically, though, documentary filmmakers shape these narratives form them, and sometimes end up neglecting the personalities of their subjects with a dreary obedience to traditional narrative form and an overly literal pursuit of objectivity (provided, mundanely, by an assortment of talking heads or an over-reliance on archival footage). Beats Rhymes & Life avoids the pitfall that many documentaries succumb to, especially music documentaries—it does not always strive for an objective portrayal of the facts, instead relying upon its own electrifying cast of characters for a certain account of the facts. It's a human drama, and it never tries to pretend otherwise.

This becomes especially clear in the case of Ali Shaheed Muhammad, the group's DJ, who remains a cypher throughout the film. This could have been a drawback if it had been a deliberate attempt on Rapaport's part to foreground the two larger-than-life MCs. But Muhammad is given numerous chances to speak for himself and, instead of giving in to the vicious rivalry erupting between Q-Tip and Phife Dawg, remains neutral, peaceful, respectful and admiring of them both. He is, as Phife's wife notes at one point, a friend unfortunately caught in the middle; when Mary J. Blige showers praise upon Muhammad and A Tribe Called Quest at one point (he's helping to produce one of her albums), he simply smiles, somewhat sadly, aware that they've made incredible music and have degenerated into a squabbling family. The most powerful moment in the movie may be a candid shouting match between De La Soul's Posdnuos and Q-Tip in a backstage room at the Rock the Bells tour; while the two musicians lament what A Tribe Called Quest has come to, the camera happens to pan across Muhammad's face—then stays there. The two outspoken men remain off-camera as Muhammad stares at the ceiling, obviously frustrated but saying nothing. He appears oblivious to the fact that the camera is recording him, which, maybe, is why he offers such a humane and subtle expression of annoyance and sadness. Like Q-Tip and Phife Dawg, Muhammad exhibits a lived-in, vivid personality that remains unknowable, and it's a testament to the movie that it respects his privacy, never trying to pry from him a testimony he wouldn't otherwise give.

After all of this candor, this unflinching study of a group in dissolution (and from a diehard fan, no less), the ending of Beats Rhymes & Life seems to stumble a bit. The movie does not conclude with the disheartening Rock the Bells tour in 2008—an epilogue actually picks back up in 2010, when a seriously ailing Phife discovers that his wife happens to be a perfect match for the kidney transplant he needs to survive. An excellent (and surprisingly powerful) scene in the hospital shortly before Phife's operation reveals to us that Q-Tip sent a brief text message to Phife (which remains unseen to us)—nothing elaborate, just an amicable reaching-out, wishing him luck with the transplant. I wish the movie had ended here: on a note of optimism, with Phife realizing how blessed he is with a loving family and recovering health (and hinting towards the reconciliation that Phife and Q-Tip may still work at).

Instead, the documentary follows A Tribe Called Quest as they reconvene for one last tour (this time in Japan). As the group plays to sold-out stadiums and (somewhat absurdly) practices their choreography at rehearsals, Rapaport seems to suggest that the magic has been recaptured, that A Tribe Called Quest may be in the middle of their comeback. (An onscreen title even informs us hopefully that Tribe still has one record remaining on their original contract with Jive Records.) I understand (and sympathize with) Rapaport's desire to celebrate the group's reunion, but a lot of onscreen evidence in this last sequence simply doesn't support it. When Phife and Q-Tip initially meet again, for example, they nod tersely and embrace briefly; then Tip simply walks away to shake hands with Muhammad. Some canny editing tries to convince us that the group's Japanese tour is as electrifying as their original shows in the early 90s, but we're not fooled: the group obviously (and inevitably) just doesn't have the spark they once did.

But even if the end of the movie's rose-colored optimism is unconvincing (and too self-conscious), we are still reminded of the heights that hip-hop can rise to at its best, and we (arguably) also realize that no rap group since Tribe has come close to matching their playfulness, their eccentricity. Indeed, by trying to make Beats Rhymes & Life appeal to everyone imaginable, Rapaport may have made a documentary that's almost too streamlined for this one-of-a-kind group. (Imagine, for example, a film that would have played on the level of “Check the Rhime” for 100 minutes.) But, as mentioned before, Beats Rhymes & Life is trying to tell a larger-than-life human drama, not blow your mind with some Sun Ra-ish fantasia, so I suppose it doesn't make sense to criticize it for being overly conventional. Earlier masterpieces like Scratch and Style Wars—the two best movies about hip-hop ever made—strike an extraordinary balance between mass appeal and one-of-a-kind, mind-bending styles; Beats Rhymes & Life manages a feat that's nearly as impressive—fleshing out the human drama behind one of the most legendary groups in the history of rap.

Aug 13, 2011

New Releases: 'The Future'

The release of Miranda July's The Future (her second feature film after 2005's Me and You and Everyone We Know) has re-instigated the common critique that the writer-director is too “twee,” too “precocious,” or too “quirky,” especially for the emotional sweep and the thematic heft that she's attempting. As in 2005, July's haters have come out of the woodwork, and there's a trace of sexism in many of the criticisms heaved her way. (David Edelstein's review in New York Magazine claims that July has a gift for going back in time and evoking the “helpless little girl she once was,” for example.) After all, July's style doesn't really seem much more precocious than Wes Anderson's, although the two directors get varying degrees of mileage out of their hermetic worldviews.

The quirkiness of The Future (like that in Me and You and Everyone We Know) is a double-edged sword: at times it comes off as too self-conscious, as its own form of empty showboating, but without this brand of daffy eccentricity neither movie would be as singularly effective. I still detest the scene in Me and You in which the adorable little boy and the frigid art curator meet on a park bench as the music swells, realizing that they've been exchanging bizarre scatological come-ons with each other in an online chat room. But this same little-boy character and his frizzy-haired precociousness also make for the movie's overwhelming final scene, which stems from a concept that could be deemed “cute” but which strikes us with its wide-eyed curiosity with the world and its subtle interconnectedness with what has come before it.

Similarly, much of The Future threatens to be unbearably quirky. Its two main characters are melancholy, awkward wannabe-artists (July's Sophie and Hamish Linklater's Jason) who speak in deadpan non-sequiturs. They are mortified by the prospect of adopting an aged cat with renal failure, though they've committed to adopting it and have about a month to fret about their mortality and impending responsibility before they can take the cat home with them. Said cat, named Paw Paw, sporadically narrates the film's proceedings in warbly monologues (delivered by July herself), accompanied by adorably DIY shots of enormous cat paws nudging their way across crumpled newspaper. This isn't even to mention the liberal sprinkling of melancholy surrealism spread throughout the film, such as a talking moon with the voice of a gentle old man offering sage life lessons, a cherished T-shirt crawling its way across Los Angeles to be with its former owner, or a little girl who buries herself up to her neck in her backyard simply, it seems, to dabble in some attention-craving performance art.

This last scene is probably the weakest in the movie: the little girl is so nonexistent as a character in the film that her stunt has no discernible emotional or thematic value. True, this little girl is the daughter of a middle-aged man with whom Sophie initiates a desperate affair, so the stunt can be rationalized: just as Sophie callously throws herself at a stranger in an attempt to escape her mundane life, so does the little girl submerge herself as a way to express her vague dissatisfaction with her home life. I guess. Thing is, we have no way of reading the daughter character, so this sequence comes off as nothing more than yet another off-kilter gimmick on July's part.

Most of the other set-pieces in the film are, thankfully, more effective. In particular, Jason's inexplicable ability to stop time—especially after he discovers Sophie's infidelity (in a way)—is a powerful illustration of his fear of aging and his debilitating emotional fragility (and makes for the most beautiful image in The Future, as Jason eventually must push and pull the ocean's tides back into motion in order to kickstart time). And the aforementioned crawling T-shirt, once it finally finds its way back to Sophie, emboldens her to finish the dance she's been trying to perform throughout the entire film—an idea which probably sounds insanely corny but which is actually hauntingly beautiful, as July gyrates and contorts herself painfully from inside the folds of the fleshy yellow shirt. The Future has its weak moments, to be sure, but it has many more strong points—strong because the absurdity is so attuned to the fears and delusions undergone by the two leads.

In many ways, Sophie and Jason are unlikeable, self-obsessed, immature idealists. They simply expect life to lead them in the right direction, and are so naively convinced of the beauty and creativity that they have to offer other people that they are baffled when they are unable to spontaneously create it. That sounds like the kind of creative block that artists in particular suffer from, but July suggests that it's really a problem shared by her (and my) generation: late-twentysomethings to forty-year-olds, who may be so overwhelmed with what's expected of them (find a job, start a family, make money) that, at some point, they give up and simply allow time to run its course. This isn't to excuse them: it's an irrational form of irresponsibility, and if Sophie and Jason stayed this way throughout the whole film, The Future would be unbearable. In some ways, though, July's film actually seems like a condemnation of people who are perpetually precocious, desperately whimsical, obliviously flighty—the very traits for which July is typically criticized. But both Sophie and Jason do genuinely seem to go through transformations, and while genuine character arcs seem increasingly hard to come by in modern (American) movies, it's something almost effortlessly (and indelibly) achieved by July in The Future. Sophie, desperate to give her life a violent jolt, does so recklessly, maybe self-destructively—afraid of complacency, she embraces the first impulse that comes to mind. Jason, meanwhile, is initially horrified at encountering the truth, at making discoveries about himself or the world around him—until he ultimately relents, submits to it, and gives in to hopeless defeatism. When both characters' overwhelming flaws re-intersect with the life of Paw Paw, that talking cat finally turns into something meaningful, genuine, and surprisingly heartbreaking—in other words, cutesiness shattering apart into a harsh, unavoidable truth. Finally, the end of the movie finds both characters at a turning point: aware of their own weaknesses, trying to decide whether they should remain imprisoned in their own insular worlds or actually try to change them through their own actions. Assuming July actually is as precocious or twee as everyone accuses her, we might read The Future as a self-reckoning (or, just as admirably, a direct and emphatic rebuttal to her critics): for those who think life is a wonderland full of affectation, time will prove you devastatingly wrong.

May 25, 2011

A Face in the Dark

Below is the second chapter of a short story that I've been working on. The first chapter was published on this blog in early December.

Chapter two 'a certain logical conclusion'

His face was thin and sallow, with deep, cutting wrinkles on either side, running from underneath the eyes to just above the chin. His mouth was firmly set into a displeased, dour grimace, stretching pronouncedly downward at the corners, which seemed to elongate the skin that covered his face, pulling it tautly over the features of his skull. He was almost hairless, with only a shadow of gray hair running up to the edge of his bald scalp. Worst of all were his eyes. Eclipsed by the sharp features of his skull, they were buried deep within a pair of black-hole eye sockets. The glint of two beady pupils, barely visible within chasms of darkness. Because the overhead light was still on in Lena's office, it cast a sharp backlight upon the man; the oblong tip of his head gleamed brightly, but his facial features could only struggle through a murky fluorescent pall. Nevertheless, I saw him now with an almost supernatural vividness. He was four stories above me, his appearance partially obscured by the reflection of city lights on the glass in front of him, but he could have been two feet away. For those features that I could not quite make out in the darkness, my brain did the rest of the work, filling in the blanks in order to complete the hideous picture. I had never seen the man before, but I was certain that the vivid picture that now arose within my mind was absolutely correct. Not once did I doubt my fleeting apprehension of him standing there, across the street, in my dead wife's office.

It was not only that I did not question the cosmic coincidence of it, it was not only that the moment's cruel illogic did not even occur to me. More than that, I immediately recognized that there was, without a doubt, a connection between this man and my wife's death. I became convinced almost instantaneously when the thought first occurred to me, with the kind of steely positivity that accompanies only those immense truths of which you become certain far before there is any tangible, concrete evidence to assure you of its validity.

Vivified, shaken awake, I spun around violently and found the nearest stairway. No time for the machinery of the elevator. I bolted through the exit door, leaped down six stairs at a time, my hands clutching the rails on either side. I almost slipped, missing stairs completely, numerous times, but I was made agile by my sudden action, impelled into swiftness. I made it to the ground floor of the hospital and raced down two hallways, oblivious to the bewildered stares and disparaging glances cast in my direction. Made it to the automatic front doors and was momentarily detained while I waited for the doors to open, impatiently. Took three bounding strides forward until I came to the curb. Glanced frenetically down the street towards oncoming traffic, then bolted into the street anyway, fairly certain that there was enough room between me and the rush of steel vehicles. Horns blared and tires screeched, but I ran madly, and made it to the curb without incident. As my right foot pounded heavily down upon the concrete of the sidewalk, it occurred to me, with a lightning bolt of rage and helplessness, that I had narrowly avoided the fate that had befallen my wife only hours earlier. Being reminded of this, my legs pumped away even more violently, and I hurtled myself forward without hesitation. I knew only that I must come face to face with the man who had materialized in Lena's office; had to become absolutely certain that he was no horrible trick conjured by my bedeviled mind.

I flung open the heavy glass door at 92011 Lexington Avenue, abruptly disturbing the sleepy silence that filtered through the lobby. The security guard at the front desk raised his head with a jolt of alarm. I glanced at him, mostly in annoyance—I had not even considered the fact that there would be anyone to impede me—and, after realizing that I couldn't possibly explain myself in my current state, simply rushed past him with an awkward gait between a walk and a run. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw him stand up in a panic, then half-jog toward the bank of elevators at the far side of the lobby to cut me off. I still avoided looking at him. He extended his right arm towards me—hoping, I suppose, that I would politely respond to his gesture and offer an explanation. He had been shouting at me ever since I entered, but I didn't have the time or inclination to respond. I glanced at his belt; he had a walkie-talkie and a nightstick that I did not want to provoke him to use. He looked middle-aged, I had surmised from the split-second in which I had looked at him, and a layer of doughy fat surrounded his midsection, but I still hoped to avoid any altercation. I kept on moving forward towards the elevators, picking up my pace; the guard was only a few feet away. For a brief moment, I wondered whether I should explain to him that I was a detective who had been called out for some semi-plausible reason, but I then remembered that, in the disorienting rush of events that had confronted me that night, I had never even thought to bring my badge with me. I concluded that this security guard would be hard-pressed to believe that this frenzied character running through the lobby was, in fact, an officer who inconveniently had forgotten to carry his identification.

Finally, we met, he and I, less than ten feet from the row of elevators, and he placed his hand roughly on my right shoulder. I took half a step back and looked him in the eyes for the first time. First, I saw panic, then fear, then simple curiosity; he was ready to restrain me forcefully, if necessary, but at this point I did not yet pose a physical threat. Only an abrupt intrusion. I empathized with him, this man who had simply come to work and had expected yet another night of dull, uneventful surveillance; but I didn't forget the face of the man who had forced me to race here so single-mindedly, and I knew I needed to get to the eighth floor without delay.

“What do you want?,” the security guard asked.

I wondered whether I should try to explain what had actually happened as concisely and reasonably as I could, but immediately recognized that, even if he did happen to believe me, my hurried anecdote would cost me too much time. In any case, I severely doubted my ability at the time to speak cogently and sanely, and even questioned whether or not my mouth would be able to perform the physical actions required to voice the words conceived of by my brain. So after a moment of awkward and alarmed silence, a jumble of words, the first things that came to my mind, spilled out.

“My wife...Lena Davenport, she works here.”

I left it at that, and the guard continued to gape at me in bewilderment. Finally, he nodded slowly and exaggeratedly, as though he needed to slow down and emphasize everything he did in order for me to comprehend. Maybe he was right.

“Okay...is she here now? Do you need to see her?”

I didn't want to explain myself any further, so I jerked my head away from him and took one assertive step forward towards the elevators. He took two quick running steps after me and placed his hand on my shoulder again, tugging roughly, spinning me around towards him.

Before I knew what I was saying—before I thought about how mad I would sound—nonsensical words that approximated my insanity began to ooze from the space between my lips. “There's a man in her office. I've seen him. Just now.” I turned around, walked again towards the elevators, was close enough to lean over and press the button.

The man swore at me, his frustration growing by the second. “Listen, you're gonna have to explain.” He stepped after me; his black boots clicked loudly on the floor. The echoes reverberated.

I didn't turn around to face him, and in mid-step I responded, “I don't have time to explain.” I leaned over and pushed the button placed halfway between the two elevators before me. The circle with an up arrow emblazoned on it suddenly illuminated itself. A digital readout above the elevator began counting down from the twenty-first floor. I felt a rough hand on my shoulder again, as I heard the guard behind me unclasp his walkie-talkie from his belt and a burst of static erupted from it. The man said, “John, I may need you in the lobby, I think I have a situation here,” and the series of words sounded entirely abstract and ludicrous to me. I was, it now seemed, a “situation”; the revelation amused and infuriated me at the same time.

While I waited for the elevator to descend, I came to the conclusion that the man behind me did, in fact, deserve an explanation, or at least that a fumbling half-explanation of my frenzied state of mind would allow me to think through my discombobulation. So lethargically I planted my left foot and spun on my right heel, pivoting in the man's direction. I remember thinking, halfway through this movement, that I should have been tired, emotionally if not physically, and it's true that a dull throbbing ache was rapidly spreading throughout my legs and calves, but my mind was overworking itself into hyperactivity; it was as though I was coursing to the peak of a caffeine fix, my heart was racing and my arms and hands were twitching and moving of their own volition, and I felt idle and deadened if I didn't just force myself to do something.

I turned towards the guard and I'm sure he recognized my current state of anxiety. To my surprise—and, I can only assume, to his as well—we traded looks for a long, silent interval, as though we realized that verbal communication would accomplish nothing and tried to fathom each other through piercing observation. What would I have seen if I had been in his place? I'm unnerved by what that image may have been: desperate, pleading, beseeching him to trust the madman in front of him. He, meanwhile, remained at least as curious as he was alarmed, and although he still held the walkie talkie in his hand, ready for a response, and his other hand hovered over his nightstick, and his eyes flicked back and forth between mine kinetically, there seemed to be some compassion in his uncertainty. I may have been incomprehensible and frenetic, but he seemed to detect that that precarious state had been instigated by something tragic, awful, intense. Maybe the empathy that I saw in his eyes was only a product of my own imagination; maybe I convinced myself, within fleeting moments of meeting this stranger, of the sensitivity and rightness of his character, simply because I wanted to believe that this man would provide a humane counterbalance to the rest of the night.

Before realizing how unstable I would sound, I tried to reassure the man before me. “I'm not crazy. Something happened to my wife tonight. And I've just seen a man in her office, a stranger, someone who shouldn't be there.” The word that had swung towards me on the doors to the room where my wife's body currently lay came back to me, all of a sudden. “This is an emergency. Really. I need your help.”

Either through compassion or exasperation, the guard who stood before me seemed to accept my state of anxiety as a plea for help. His left hand, which had been hovering over the club hooked into his belt, slowly moved forward towards me, and the palm stretched itself out in a gesture of consolation. He half-opened his mouth, about to respond, when the walkie-talkie in his right hand erupted with a blip of static and a harsh alien voice. It must have been “John”—some agent of authority hovering above me somewhere in the building. In my irascibility, I assumed that John was only waiting for a transmission like this from my security guard, a transmission that would allow him to exert some unrestrained yet justified force. John said: “I read you, Henry. Some uniforms are on their way. I'll be right down, try to detain the situation. Over.” Despite my distress, I chuckled at his sign-off, at the pleasure I assumed he felt at uttering it so officiously.

No response from my brother Henry was necessary; he hooked the walkie-talkie back onto his thick black belt. Now, I was sure, panic mode had given way to overwhelming curiosity. Meanwhile, the elevator was on its way; it had just passed the tenth floor. Two more floors and, maybe, the cypher I was hunting for would board the elevator. I wondered if the hideous sharp face would greet me when the doors opened. Would he take the stairs? Would he simply wait for me in my wife's office, smirking cruelly, waiting for me to confront him desperately?

Henry spoke to me now sensitively, with a voice usually reserved for socially-challenged adolescents. “What happened to your wife? Is she okay?”

After a moment:

“No.” Shook my head.

“And there's a man in her office. A stranger.”

“Yes.”

I wondered how he was going to detain the situation.

He nodded, consolatory.

“Alright. What floor?”

“Eighth.” I thought that was unclear. “Eight.”

I looked back up at the digital readout. It had just switched from seven to six. I didn't turn around, but I assumed that Henry had noticed the same thing. I wondered what I wanted, what I hoped to see when the doors opened. To see that horrible skeletal face again, in such close proximity—the thought made me shudder, the idea chilled me inside; but, at the same time, nothing was of more crucial importance, to question that man, to alleviate my distress, my uncertainty. I felt confident in the power of my loss: to meet the awful hellish emptiness of his eyes with the pain of my own, I felt certain that he, whoever he was, would be unable to resist my frenzied plea for answers.

Henry and I remained locked in this curious dual pose: me, head arched upwards towards the digital readout, hands clasped within one another, skin rubbing against skin, restless; him, standing behind me, presumably in a similar pose, waiting in anticipation for the elevator to alight. The silence that drifted throughout the lobby was distinct and abrasive; hums of heaters and fluorescent lights commingled to create a devilish chord. Never before had a handful of brief moments seemed more like a taunting eternity.

Before the uniforms had a chance to arrive, the elevator finally counted its way down to three, then two, then L. Only a few seconds elapsed until the foreboding metallic doors churned open, but in these few seconds a whirlwind of doubts and anxieties flickered through my tortured head. What would I ask the man before me, if indeed he was waiting within the elevator when it opened? What basis did I have to suspect him of my wife's death, besides the taunting coincidence of his appearance in her office so soon afterwards? In those few haunting seconds, two images flitted back and forth before me like the pages of a flipbook, skipping kinetically: one, a face of pure evil and cruelty, glaring at me, haloed by the sickening glow of fluorescent office lights; the other, Lena's face as she smiled at me in her happiest moments, beaming carelessly. It sickened me to see these two faces intercut with one another, dissolving into one and the same creature; good, evil; until my mind could no longer distinguish one from the other, and I suddenly, in disorientation, forgot which face I expected to greet me when the doors of the elevator opened.

They opened, at last—more slowly than usual, I thought, as the metal doors lazily churned aside. Inside, the image that met me was deflating: nothing, a pocket of fluorescent light, no body, nothing. The spark of desperate outrage that had compelled me in the first place was now suddenly extinguished, crushed out by prolonged uncertainty, ignorance, helplessness. Anything—any altercation, inconceivable revelation—would have been better than this nothingness, any face better than the hollowness of that elevator.

I was snapped out of my dejection by a slight cough behind me; Henry cleared his throat, almost politely, I thought. His forced noise was inquisitive: inside the noise was an unasked question—was I crazy? Did the man I was looking for exist?

I placed my right hand against the elevator door to keep it from closing, and I pivoted back towards Henry, looking him in the eye. The skittish, desperate energy with which I had burst into the building was now gone; my exhaustion, and my encroaching doubt, had flattened it into meek and deluded hope. There was a shrug in my eyes as I turned to Henry, and he simply kept that pose of readiness, confusion, alarm, and sympathy.

“I need to see her office,” I said. The life was gone from my eyes but there was still an aching urgency in my voice. Henry nodded and walked past me into the waiting elevator car.

“Alright then,” he said.

The enormous door began shoving restlessly against my arm as I held it open, and I stepped inside after him. The doors closed behind us. We traveled the eight floors in silence. There was syrupy and absolutely hellish jazz music oozing out of the speakers. The floor under us was a thin blue-and-gray carpet that seemed to soak up the nauseating light like a sick sponge.

On the eighth floor, the doors spread open with a ding. Across the hallway was an elegant desk with a light-blue glass top, and behind it a series of cracked glass panels that obscured the dark offices within. On one of these panels was a board listing office numbers and employees' names, with the name and logo for Perpetua Financial Consulting etched across the top. I stepped wordlessly from the elevator and peered at this list of offices; Henry unhooked a flashlight from his belt and swept it down the hallways, illuminating only a dim and eerie intersection of drab office architecture. I squinted, and in the dim light that still filtered there, I could make out her name—Lena Davenport, #817D. It offered a small reassurance that I had remembered her office number correctly—at least this was a sign that I still had control of my mental faculties, I told myself. Then a cruel realization followed: if this was true, if I hadn't simply been the victim of illusion and warped hallucination, then that man had in fact been in my wife's office. May still be there now. I stepped off quickly to the right. Henry followed me. The floor was made of smooth white tile and the footsteps of our shoes clacked in echo of each other—loud high ominous reverberating clicks. We worked our way down half of another hallway when we both realized that a sharp fluorescent light was slanting towards us from the intersection of another hallway. The light was on in one of the offices. We walked hurriedly down the hallway, took a sharp turn into another, dread and urgency commingling. The office light was emanating from behind a thick glass door at the center of this hallway. I took a step forward until I felt Henry's hand on my shoulder; he gently held me back and stepped in front of me, flashlight extended and what looked like a taser gripped firmly in his other hand. Apparently he didn't doubt my story any more, and although, in any other situation, I may have resented his overeager vigilance, here I welcomed it. We neared the door to a bank of offices, one of which, we could now see, was harshly lit by a single overhead light. Its door gaped open forebodingly—a warning.

I glanced at the number stenciled next to the outer door as we approached it: 817. As Henry pushed against the door with his outstretched flashlight—unlocked, it swung easily open—I could squint into the yellow light and make out the smaller number next to the inner office. 817D. My wife's office. Her name was painted on the wall next to the open door.

Henry stood there for a moment, holding the door open with his body, his gaze still firmly locked on the open office door and the light that cut through it. I could tell he was scared. So was I. I wished I had brought my gun.

I slipped past the open door, past Henry, and took three long uncertain strides towards Lena's office. The sound of my footsteps disappeared into the thick carpet. Henry walked up beside me. I was close enough now to see inside the office, through the half-open door; but all I could make out was a thick old mahogany desk, the side of a bookcase, and diluted neon lights filtering in from the city outside. I reached my right hand out, pushed gently on the door, and opened it the rest of the way. I couldn't hear Henry breathe.

The door made no noise as it swung open until it tapped lightly against the wall. Lena's chair, behind the desk, its back to the row of windows, was empty. There were two dark red padded chairs on the other side of the desk, facing the windows. There was a man in one of them. He was not moving. He was sitting and looking out the window. I could only see the back of his head. He was almost bald and the tip of his head came to a sharp and ugly point. Thin, short black-gray hair ran up to his scalp. He was an ugly silhouette. There was a file open on the desk—Lena's desk.

Henry stepped up next to me. He saw what I saw. I heard him unable to suppress a gasp.

I took one more decisive step forward and rapped loudly on the door as I passed, wanting to make our presence known—as though the man before us was somehow not aware of it. He still didn't move. My eyes darted to the reflection of his face in the window; it was smudged and distorted, but it seemed to be the same hideous face that had returned my stare minutes earlier. I kept taking half-steps forward in trepidation, but his absolute stillness was beginning to make me shudder. It could have been a skeleton sitting before me.

“You,” I finally said, absurdly. Henry stood standing at the doorway. The figure didn't move. “Get up.”

No one moved for a long moment. Slow deep breathing and melodic city sounds were all that could be heard. Then finally the man placed both hands on the armrests. He stiffened his arms and pushed himself up. He stood facing the windows. He was incredibly tall, and the ceiling light, mere feet away from his bald sloping head, struck him harshly, and a horrible jagged shadow was cast across the office floor.

“Turn around,” I said.

The man obeyed, pivoting towards me slowly. Though I tried to interpret some emotion from the features of his petrified face—I expected, I suppose, a look of gloating condescension or merciless self-satisfaction, something that would betray his guilt—the man's skeletal face told me nothing. He simply returned my inquisitive gaze, though his eyes were lifeless. His hands hung awkwardly at his sides as he stood there, absolutely rigid. The suit he wore was an elegant dark gray, well-tailored, but somehow it still seemed too small for him.

I didn't know what to ask him, what to say—too much was on my mind. I began with the most obvious question I could think of.

“Who are you?”

The man stood there blankly for a moment—either unwilling to answer or unsure how. I could sense Henry standing next to me.

Finally, the man responded. His voice was as guttural and monotone as I had presumed it would be.

“My name is Mark Voland. Who are you?”

Before I could answer, a harsh burst of static erupted from Henry's walkie-talkie, followed by the voice of the man that Henry had contacted earlier: “John,” the top-middle-level security officer who I had imagined cooling his heels in some dank room outfitted with a bank of television monitors. “Henry, I've got two officers in the lobby down here,” John said. “Where are you? Is the situation under control?”

Without peeling my eyes away from the man before me, I heard Henry unclip the radio from his belt and take four long strides out of the office. Henry's response came from the outer office a few feet away, muffled: “Not exactly. Come up to room 817D now. There's someone here.”

A moment later, John's response: “Copy. We'll be there as soon as we can.” Another blip of white noise and the radio became silent. I waited for Henry to return to the office until I addressed Mr. Voland. My confidence was slowly rejuvenating itself within me, and I could feel a hot white energy rising inside of me again—the same kind of wild anxiety that I had felt upon seeing that face less than twenty minutes beforehand. I wasn't crazy, I could now tell myself with certainty; the man before me was not a phantom. I took a step towards him. He did not react.

“What are you doing in my wife's office?”

I thought this question would affect him somehow; if he really didn't know who I was, and if he had had anything to do with Lena's death, surely he would not have been able to conceal some kind of surprise at discovering that I was her husband. But as I peered desperately at him, I realized with dismay that, again, I could not read any discernible reaction from his stone-set features. I had spent the last six years interrogating suspects, reading and interpreting their reactions and gesticulations, studying the physiological behavior of people who lie, and I believe I can claim, with no boastfulness, that I have become an expert on visible human behavior and the ways in which it reflects those psychological undercurrents we would rather keep concealed. I could read nothing on Mr. Voland's face, besides a haunting emptiness.

“Lena Davenport is your wife?”

I was going to say was—not is—but instead I just nodded. It was then that I believe I detected the first trace of an emotion on his face: a smile.

“What are you doing in her office?,” I repeated.

He sighed, then, as an answer, reached behind him and picked the manila file folder off of Lena's desk. It was an enormous file, overflowing with sheaths of paper and color-coded Post-It notes that were overloaded with my wife's frantic scribbling. I grabbed the file from him, with some reticence, and noticed the name written upon the blank tab: Consolidated Metropolitan Insurance. My eyes shot up to Mr. Voland's face once more.

“This is the case your wife has been working on. Have you heard of my company?”

“Your company?,” I asked, unable to suppress my astonishment. “You own Consolidated Metropolitan?”

He shook his head, though his eyes did not leave mine for a second. “No. I'm just mid-management. Low on the totem pole. But two of my colleagues and I have been meeting with Mrs. Davenport—with your wife—in a consulting capacity. Maybe she's told you...our company has been experiencing both legal and financial difficulties recently, and she's been helping us—well, you know, get ourselves out of the red.”

I glanced at a few of the papers that I currently held in my hand, but they were banking ledgers, accounting statistics, information regarding insurance policies and potential payouts versus foreseeable profits, and so on—they may as well have been written in a foreign language. I took another step forward, reached past Mr. Voland, and threw the file back onto Lena's desk.

“Okay, you're a client of my wife's. That still doesn't explain why you're here.”

“Well, we had a meeting this afternoon. Or yesterday afternoon, I guess. Maybe she told you?”

He seemed to expect an answer, but there was something impertinent, even mocking, in his question. He must have known about my wife's death; another fraction of a smile crept across his face, and I was sure that he was taunting me.

I didn't answer his question, so he continued: “The meeting went late, and we must have left around 5:30 or so. My two colleagues and I had a drink around the corner. It was a celebration, I suppose—things started to seem promising, you know? Mrs. Davenport is incredibly good at her job, I hope you know. So we had a few drinks and then were going our separate ways. I was walking home and was passing by—” (he turned his head around and arched it towards Lexington Avenue, eight flights down from us) “—right down there in front of the building, when something occurred to me. Mrs. Davenport had suggested a course of action involving subrogation of corporate entities who had been responsible for certain losses that had been incurred by our clients. Do you know insurance fairly well, Mr. Davenport?”

“No.”

“Well...I don't want to bore you with the specifics. To put it simply, Consolidated Metropolitan had compensated some of our individual clients for certain policies—health insurance, unemployment, liability, things of that nature—when in fact I thought we could prove that certain corporate parties could be held responsible for the losses that those individuals had incurred. Lena pointed out that we were within our rights to pursue legal action against these corporate entities, as long as we could document, in court, their culpability regarding our clients' payouts. About three hours ago, as I said, I was passing by across the street there, when certain policies came to mind—namely health insurance policies for construction workers who had experienced some respiratory problems after working at a job site just north of the city. We were unable, at the time, to prove that their employers had knowingly put them at risk, but we had always thought that the documentation supplied to us by those employers was somewhat specious, and Mrs. Davenport agreed with us after we showed her the risk assessments that the construction company had supplied us with.”

I was growing tired with his lengthy response, and I wondered if he wasn't trying to talk circles around me—impressing me with the minutiae of insurance coverage while avoiding an explanation of why he was actually in Lena's office. So I said, simply, “So?”

“So, I came back up to her office before going home, hoping to catch her at work and hopefully come up with another solution before calling it a night. I don't know if that makes sense, considering we had already been discussing possible solutions all afternoon, but I hope you understand that Consolidated Metropolitan is more than simply a job for me; I've been an employee since the company was founded four years ago, and I've been a witness as the company made some unforgivable mistakes and, in a way, dug its own hole. Anything I can do to help the company, to restore the potential we once had, I will do, and the opportunity to do so earlier tonight proved too propitious to resist.”

I balked at his wording; I wondered if someone in his position would actually explain himself so convolutedly, with such rehearsed precision. As I mentioned, I had had considerable experience in observing the gestures, the oversights, the slips of the tongue, of criminals and liars and people with something to hide; and I had encountered numerous people who had explained themselves with similarly ostentatious rhetoric. In almost every case, they had had plenty of time to rehearse their defense, and had made the mistake of scripting their own dialogue with overzealous exactitude. I distrusted him now more than ever; his defense was self-incriminating.

“What time did you come back up to my wife's office?”

“Uh...it must have been about ten.”